By Dr. Edward M. Sullivan, Ph.D

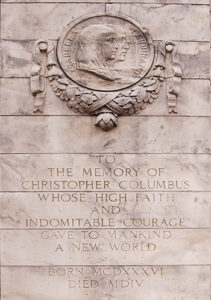

On the north side of the Columbus Memorial, the side facing Union Station, there is the following inscription:

TO

TO

THE MEMORY OF

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS

WHOSE HIGH FAITH

AND

INDOMITABLE COURAGE

GAVE TO MANKIND

A NEW WORLD

BORN MCDXXXVI

* * * * *

DIED MDIV

* * *

The faith of Columbus is given more explicit definition in the preamble to the by-laws of the National Columbus Celebration Association: “The Association seeks to honor not only the memory of Columbus and his historic achievements in linking the Old World and the New, but also the higher values that motivated and sustained him in his efforts and his trials. Those virtues–faith in God, the courage of his convictions, dedication to purpose, perseverance in effort, professional excellence, and boldness in facing the unknown–are as needed as ever today and in the future.” This Columbus Day 2001 marks the 500th anniversary of the Discoverer’s most elaborate and significant written expression of his faith. It is a document that librarians have named the Libro de las profecías, or Book of Prophecies, much ignored by historians until relatively recent years, though it probably provides the best insight available into his thinking and motivations. Here we look at both that document and the faith of Columbus that it expressed.

At the end of September 1500, Columbus had been brought back from Santo Domingo in chains. The royal court was at Seville, and he stayed for a number of months at the Carthusian monastery of Las Cuevas across the Guadalquivir River from the city. There he developed a collection of detailed notes which he himself described as “A notebook of authorities, statements, opinions and prophecies on the subject of the recovery of God’s Holy City and mountain of Zion, and on the discovery and evangelization of the islands of the Indies and of all other peoples and nations.”(1)

These notes were to form the basis for a long poem to be presented to their majesties. That, however, was never done, though the notes apparently were presented to them with a covering letter. Completion of the project may have been set aside for the sake of preparations undertaken in March 1502 for the fourth voyage, for which he left Seville on April 3, and set sail from Cadiz on May 9. (In any event, it seems to have had no effect on the sovereigns.)

The Libro is a manuscript of eighty-four folios containing a collection of quotations in Latin (with a few pages of Spanish poetry), mainly from the Bible, but also from the Fathers of the Church and a number of other ancient and medieval writers. They were apparently dictated between September 13, 1501 and March 23, 1502, mostly to his son Ferdinand, and his friend the Carthusian monk Gaspar Gorricio, with a lesser amount to his brother Bartholomew and a part of it in his own hand.

The Main Themes

The central ideas of the Libro are: (1) his own special vocation–confirmed both by his personal experiences and by what he has been enabled to do in fulfillment of prophecies–to make possible the evangelization of all peoples; and (2) the vocation of their majesties, according to prophecy, to recover the Holy Sepulchre and Mount Zion, which the wealth from his discoveries will make possible, and the success of which is promised by the demonstrated fulfillment of prophecy in his own case. All this is to take place before the end of the world, calculated by him on the basis of some of the authorities quoted to be 155 years away at the time of writing in 1501.(2)

Thus, Columbus saw himself as a man especially chosen by God for a mission–not just to discover a new route to the Indies, or even new lands, but by that to make possible the spread of the Faith to all, and provide a source of revenues to fund recovery of the Holy Sepulchre by the Spanish majesties, all of which had been prophesied.

Thus, Columbus saw himself as a man especially chosen by God for a mission–not just to discover a new route to the Indies, or even new lands, but by that to make possible the spread of the Faith to all, and provide a source of revenues to fund recovery of the Holy Sepulchre by the Spanish majesties, all of which had been prophesied.

The Libro has not, over the years, received much attention from historians. Indeed, it was first published only in 1892 (in Italian, for the Quadricentennial). The first publication in Spanish was ninety years later, in 1982, and it first became available in English just ten years ago.(3) A number of modern authors have commented that the book has seemed an embarrassment to some historians, not in keeping with the idea of Columbus as exemplar of a modern scientific approach to the world, revealing instead a more medieval mentality.

While it surely was, in part, an attempt to justify himself to the sovereigns after his humiliating return in chains, the evidence does not support a charge that such was the primary intent, or that the Libro was insincere at best. But Columbus was, under the circumstances, quite naturally interested in defending himself. A second and quite different document, apparently begun in 1497 and completed in 1501 and called the “Book of Privileges,” is a collection of evidence in defense of his claims to titles and financial and other rewards from the crown for himself and his progeny. Though his expectations of fulfillment were unrealistic, “the case is fairly convincingly made” according to Kirkpatrick Sale, an influential critic of Columbus at the time of the Quincentenary.(4)

A Man of Faith and Piety

The themes of the Libro were the themes of, and consistent with, Columbus’s whole life. Delno West, in his introduction to the English publication of the text, says “…that the vision of Columbus was one of a missionary and a crusader…. is present in writings that survive from every period of his life, in notes written on the margins of books he owned that are dated as early as 1481, and in letters to a wide range of people throughout his lifetime… His contemporary biographers agree in recognizing this vision and the spiritual discipline of his life….”(5)

There is no doubt today that Columbus was a sincerely religious man, who stood apart by his piety and religious observance. The best source and witness is Bartolomé de Las Casas (1474-1566), his first biographer.(6) Las Casas’s father and uncle were colonists on Columbus’s second voyage, and he himself as a young man saw Columbus in the Admiral’s triumphant days in Seville in 1493 after his first voyage. In 1500 he crossed the ocean to become a colonist himself, later deciding to become a priest. After being ordained in Rome, in 1510 he was the first priest to celebrate his first Solemn High Mass in the New World, later (in 1522) entering the Dominican Order. In 1514 when he was 40 he had came to see that “everything done to the Indians in these Indies was unjust and tyrannical” and “decided to preach that,” the defense of the Indians becoming a life’s work.(7)

Las Casas crossed the ocean ten times in his long life, traveled extensively in the New World as a missionary, and in the fourth decade of the century became bishop of Chiapa in southern Mexico. He authored a number of works, including a “History of the Indies” (dealing with the twin themes of Columbus’s discovery and the fate of the Indians), and an abstract of Columbus’s journal of his first voyage, the closest thing we now have to the Admiral’s now-lost journal. It appears that he did not personally know Columbus, but that he did know well both of the Admiral’s brothers, Bartholomew and Diego, and both of his sons. Diego and Ferdinand.

Columbus was a hero to him, but on the other hand he was critical of the Admiral as an administrator and even more so for some of his behaviors toward the Indians, as will be clear shortly. With these mixed feelings, Las Casas’s description (in Book 1, Chapter 2 of his History) of Columbus’s faith and piety, as well as his criticisms of Columbus, are worth extended quotation. First, as to his piety:

In matters of the Christian religion, without doubt he was a Catholic and of great devotion, for in everything he did and said or sought to begin, he always interposed “In the name of the Holy Trinity I will do this,” or “launch this” or “this will come to pass.” In whatever letter or other thing he wrote, he put at the head “Jesus and Mary be with us on the way,” and of these writings of his in his own hand I have plenty now in my possession. …

He observed the fasts of the Church most faithfully, confessed and made communion often, read the canonical offices like a churchman or member of a religious order, hated blasphemy and profane swearing, was most devoted to Our Lady and to the seraphim father St. Francis; seemed very grateful to God for benefits received from the divine hand, wherefore, as in the proverb, he hourly admitted that God had conferred upon him great mercies, as upon David. When gold or precious things were brought to him, he entered his cabin, knelt down, summoned the bystanders, and said, ‘Let us give thanks to Our Lord that he has thought us worthy to discover so many good things.’ He was extraordinarily zealous for the divine service; he desired and was eager for the conversion of these people [the Indians], and that in every region the faith of Jesus Christ be planted and enhanced. And he was especially affected and devoted to the idea that God should deem him worthy of aiding somewhat in recovering the Holy Sepulchre….

He was a gentleman of great force of spirit, of lofty thoughts, naturally inclined (from what one may gather of his life, deeds, writings and conversation) to undertake worthy deeds and signal enterprises, patient and long-suffering (as later shall appear), and a forgiver of injuries, and wished nothing more than those who offended against him should recognize their errors, and that the delinquents be reconciled with him; most constant and endowed with forbearance in the hardships and adversities which were always occurring and which were incredible and infinite; ever holding great confidence in divine providence.”(8)

Samuel Eliot Morison, a more modern biographer, gives a summary:

Columbus was a Man with a Mission, and such men are apt to be unreasonable and disagreeable to those who cannot see the mission…He was Man alone with God against human stupidity and depravity, against greedy conquistadors, cowardly seamen, even against nature and the sea.

Always with God, though; in that his biographers were right; for God is with men who for a good cause put their trust in Him. Men may doubt this, but there can be no doubt that the faith of Columbus was genuine and sincere, and that his frequent communion with forces unseen was a vital element in his achievement. It gave him confidence in his destiny, assurance that his performance would be equal to the promise of his name. This conviction that God destined him to be an instrument for spreading the faith was far more potent than the desire to win glory, wealth and worldly honors, to which he was certainly far from indifferent.(9)

From various sources we have record of conciliatory behavior on the part of Columbus toward people who acted against him, of his private praying of the divine office in his cabin, of daily public prayers at sea,(10) of his wearing of the Franciscan habit,(11) of his dedication of his voyages to the Trinity, of his regular naming of places in honor of God and of the saints, and of his mysterious signature that emphasized the significance of his name “Christopher” as Christum ferens, or “Christ-bearer.”(12)

(Of particular relevance to American Catholics was his devotion 500 years ago to the Immaculate Conception of Mary, a title under which this nation was dedicated to her by the American Bishops in 1847, symbolized today by the magnificent Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in the nation’s capital, a national church to which the Knights of Columbus have over the years been especially generous and especially close.[See a longer note with more information about this devotion and Columbus, and about the National Shrine.])

A Negative Side

If we have looked to Las Casas for a positive view, it is only fair to look at what else he has to say that will help to complete the picture. For that same individual seen by Las Casas as a good man, admirable in many ways, had his flaws, which the Bishop honestly criticized. Some of Columbus’s behaviors toward the Indians–though apparently consistent with widely-accepted norms of the time–were not morally acceptable to some of that era, especially Las Casas, and certainly not on accord with the moral standards of our own day.

For example, the Spanish government and Columbus both assumed they had a right to take possession of the lands and peoples in the New World. As Las Casas saw it:

Ignorance got the admiral into this error, this blindness …but inexcusable ignorance. Perhaps he made the judgment that we had more of a right to peoples in the New World–merely because they were infidel… It was because the men the Kings employed as a light to their eyes ignored, in a dark and wicked way, the injustice that went on, that the Admiral ignored it also. That he was not schooled in conscience is surely no surprise. No matter. He knew, no one better, by experience, the goodness, the kindness, the humility, the simplicity, the virtuousness of the Indian peoples. Nor did anyone but himself make this known to the Kings, to the Pope, to the world. … He himself convicts himself of great guilt. … The Admiral’s intention was good, if one looks simply at intention. And does not measure it by deed. And allows for mistake and ignorance of the law.”(13)

In fact, in the sixteenth century all theologians held that it was licit to enslave pagans (but not Christians) captured in a just war:(14)

The intense hostility, toward the end of the Middle Ages, between Christians and Muslims created a reciprocal slave market. Christian forces felt entirely free to force Moors, Turks, and Arabs into servitude. At the same time, the Muslims did not feel moral or theological inhibitions in enslaving those who did not worship Allah. If the Christians had an estate, the Muslims offered to emancipate them in exchange for a substantial ransom.(15)

Not finding the requisite conditions fulfilled in general (since the Indians were not known enemies of Christianity such as Saracens. and had committed no crime against Spain), the Spanish monarchs early on prohibited enslavement of the Indians. But they allowed for exceptions. The first exception was the Caribs, understood to be cannibals who preyed on others, and the second was rebellious Indians, according to the doctrine on pagan captives in war. The presumption that the Spanish had a right to the land in the first place was later challenged by Las Casas, who asked, ‘Those who are not subjects, how can they be rebels?’ In Las Casas’s opinion, slavery “‘was nothing more than the tacit or interpreted violation of natural law,’ which is ‘common to all nations, Christian and gentiles, and of any sect, law, state, color, and condition, without any difference whatever’.”(16)

Thanks largely to Las Casas Spain was in fact the first country to examine seriously the moral aspects of slavery and to bring about changes in thinking in this regard. In fact, in 1550-1551 there was a famous debate on the subject between Las Casas and the jurist Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda. at Valladolid before learned and high-ranking men (It was not a literal face-off, since each of the two contenders presented arguments directly to the judges rather than to each other.) Sepúlveda had espoused the Aristotelian theory of natural slavery: “that one part of mankind is set aside by nature to be slaves in the service of masters born for a life of virtue free of manual labour,” which was held “with great tenacity and erudition” by learned proponents, but scorned by many others.(17) Perhaps for the only time in history, a great ruler–in this case, Emperor Charles V, who ruled most of both Europe and the New World–called a halt to all conquests until it was clear whether they were just or not. In the end, more or less by a consensus rather than by a specific ruling, the question was settled in line with Las Casas’ position.

Regarding the slavery controversy in general, Spanish historian Rafael Altamira points out that “‘The most interesting and fundamental aspect of our colonization [of America] was the tragic debate between those who were for slavery and those who were against it”(18)

Celebrating the Evangelization of the Americas

Whatever his faults or mistakes, Columbus tried to be a Christ-bearer to the peoples in lands lying to the west of Spain. And whatever the intervening vicissitudes, one must admit that his mission was not without success. Today there are more Christians in the Western Hemisphere than in any continent in the rest of the world; more Catholics in Latin America than in any other continent, more Protestants in North America than in any other continent, more Protestants in the United States than in any other country.

The celebration of the evangelization of the Western Hemisphere was the focus of the observance of the Quincentenary by Pope John Paul II. On October 12, 1984 in Santo Domingo he addressed an audience of thousands, including about 100 Latin American Bishops, in the Olympic Stadium. He then recalled that “On the first apostolic journey of my pontificate I said I wished to pass through Santo Domingo, ‘following the route which the first evangelizers traced out at the time of the discovery of the continent.” (Arrival Speech in Santo Domingo, Jan. 25, 1979),.and that at Zaragoza in Spain he had said that the Church could not fail to share in the fifth centenary of the discovery and evangelization of America (November 6, 1982).(19)

The celebration of the evangelization of the Western Hemisphere was the focus of the observance of the Quincentenary by Pope John Paul II. On October 12, 1984 in Santo Domingo he addressed an audience of thousands, including about 100 Latin American Bishops, in the Olympic Stadium. He then recalled that “On the first apostolic journey of my pontificate I said I wished to pass through Santo Domingo, ‘following the route which the first evangelizers traced out at the time of the discovery of the continent.” (Arrival Speech in Santo Domingo, Jan. 25, 1979),.and that at Zaragoza in Spain he had said that the Church could not fail to share in the fifth centenary of the discovery and evangelization of America (November 6, 1982).(19)

He joined with Leo XIII, pope at the time of the 400th anniversary, in recognizing the providential character of Columbus’s exploit, denying neither “the interdependence which occurred between the cross and the sword during the stage of the first missionary penetration” nor “that the expansion of Iberian Christianity brought the new peoples the gift which derived from- the origins and gestation of Europe–the Christian faith,with its power of humanity and salvation, dignity and fraternity, justice and love for the New world.”

He also recalled that “in spite of the excessive closeness or confusion between the lay and religious spheres, which was a mark of that age, there was no identification or subjection, and the church’s voice was raised from the first moment against sin.” As witness Las Casas and many others.

And to the bishops of each nation he presented a V Centenary Cross. As the inscription on it proclaims, the V Centenary Cross commemorates the fifth centenary of the evangelization of the New World. It was designed to be similar to the cross planted about 1514 in Santo Domingo on the site where the first cathedral in the Americas would be erected.

On October 12, 1992, on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s landing, in Santo Domingo again he spoke to the Fourth General Assembly of the Latin American Bishops, focusing on “the new evangelization,” and as part of that the need to address “the problems relating to justice and solidarity among all the nations of America”. Also in observance of that anniversary in Santo Domingo the huge Columbus Lighthouse, designed in the shape of a cross lying on its back was dedicated.

The Quincentenary of the evangelization of Americas was adopted as the theme for the anniversary celebration by the bishops of the United States. To aid in that the Knights of Columbus had a number of replicas of the V Centenary Cross hand-made to be presented to and used in each diocese in the Americas as a focus for prayer services as part of the Quincentenary year’s celebrations.

Earlier this year, as the new millennium got underway, a new Knights of Columbus museum building at their headquarters in New Haven was opened. In its courtyard there is a new statue for the new millennium: “Columbus the Evangelizer.”

Notes

1. Christopher Columbus, Libro de las profecías, trans. and ed. Delno C. West and August Kling (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1991), 101.

2. His calculations were based on the Bible and writings of St. Augustine and several medieval authorities. As the reader may have noticed, the world did not end in 1656. But that year the Dutchman Christian Huygens, 27, invented the pendulum clock, enabling mankind to tick off the time after that more easily.

3. Christopher Columbus, Libro de las profecías, trans. and ed. Delno C. West and August Kling (Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1991).

4. Kirkpatrick Sale, The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy (New York: Alfred A.Knopf, NY, 1990). 187.

5. Delno C. West, Introduction to Christopher Columbus, Libro de las profécias, trans. and ed. Delno C. West and August Kling (Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1991), 2-3.

6. There is some confusion about his birth date, some sources giving it as 1974 and others as 1984. Without examining the merits on either side, we have simply opted for one.

7. George Sanderlin, trans. and ed., Witness: Writings of Bartolomé de las Casas (Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1992), 11.

8. The text as quoted is from the translation used by Samuel Eliot Morison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea, vol. 1 (New York: Time, Inc., 1962), .41-42. Another translation is provided by Sanderlin, 30-31

9. Morison, 42.

10. Morison, 164, notes that “In the great days of sail before man’s inventions and gadgets had given him false confidence in his power to conquer the ocean, seamen were the most religious of all workers on land or sea.”

11. West, on p. 58 of his Introduction to the Libro de las profecías, says that “there is no direct evidence that Christopher Columbus ever joined the Third Order of St. Francis (Tertiaries). But Alain Milhou and others have made a convincing case based upon circumstantial evidence found in the sources.” and that “according to legend, he was buried in Franciscan robes.”

12. Las Casas reflected on the name and what he regarded has Columbus’s providential mission furthering evangelization:

He was called, then, Christopher, that is, Christum ferens, which means bearer of Christ, and thus he sometimes signed himself. And in truth he was the first who opened the gates of this Ocean Sea, through which he entered and introduced himself to these most remote lands, and to kingdoms until then so hidden from our Savior Jesus Christ and His blessed name–he who before any other was worthy to give tidings of Christ and to bring these countless races, forgotten for so many centuries, to worship Him.

His surname was Columbus which means new settler. This surname suited him in that by his industry and labors he was the cause… of an infinite number of souls…having gone and going every day of late to colonize that triumphant city of Heaven.

The text is from Sanderlin, 29-30. In Spanish the name is Colón, a cognate of the English word “colonizer.” In Latin, however, Columbus means “dove,” reproduced in the emblem of the Fourth Degree of the Knights of Columbus, representing Columbus at one level of meaning, and the Holy Spirit at another.

13. As given in Francis P. Sullivan, S.J., Indian Freedom: The Cause of Bartolomé de las Casas, 1484-1566, A Reader (Kansas City, Missouri: Sheed and Ward, 1995), 67-68.

14. Joseph Höffner, as quoted by Luis H., Rivera, A Violent Evangelizing: The Political and Religious Conquest of the Americas (Louisville: Westminster / John Knox Press, 1992), 92.

15. Rivera, 93.

16. Rivera, 103, 96.

17. Lewis Hanke, Aristotle and the American Indians: A Study in Race Prejudice in the Modern World (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1959), p.13.

18. As quoted by Rivera, 93.

19. Origins (NC documentary service), November 1, 1984.